From Yosemite to the Darkroom: Exploring the World of Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams: Champion of the American Landscape and Master of the Zone System

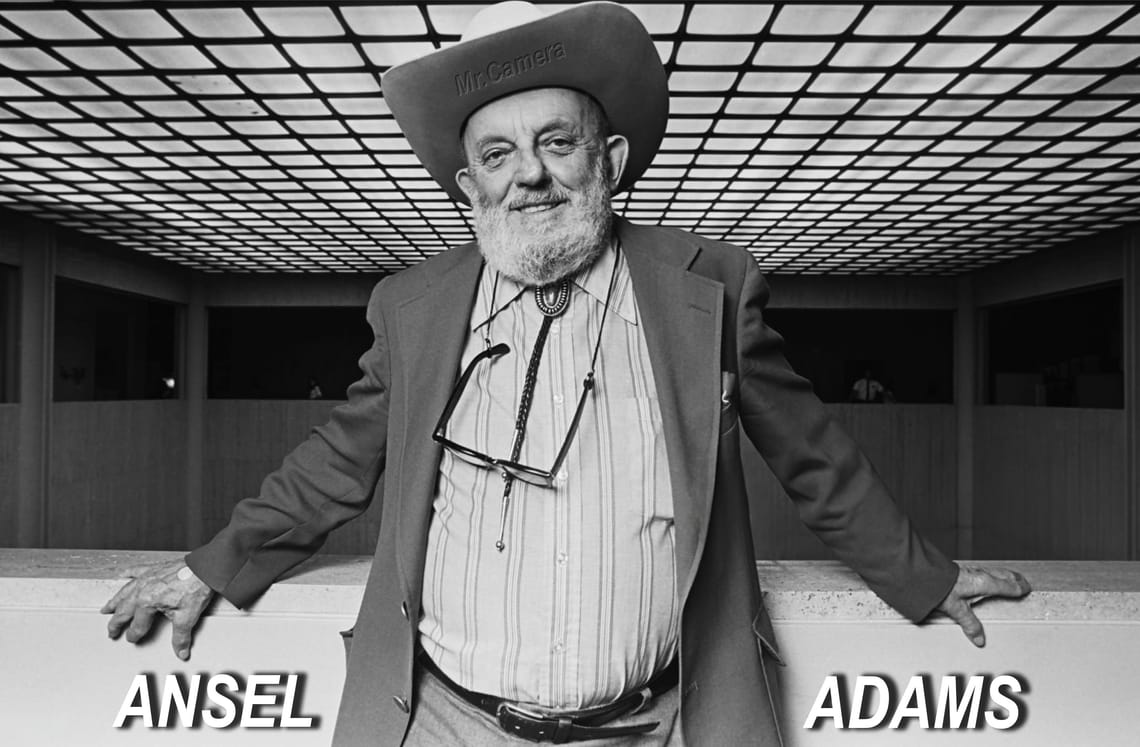

Ansel Adams (1902–1984) was an American photographer widely celebrated for his breathtaking black-and-white images of the American West, especially Yosemite National Park. He devoted his life to exploring the intersections of art, nature, and conservation, shaping modern photography techniques while also advocating for environmental preservation. Born in San Francisco, Adams grew up in a time of rapid change—industrial innovations, shifting social norms, and a growing national fascination with the natural world. These factors sparked his curiosity and fueled his devotion to capturing the grandeur of landscapes with both technical mastery and artistic passion.

Early Life and Influences

Adams was born on February 20, 1902, to a relatively affluent family. When he was four, he suffered a severe injury after an earthquake in 1906 threw him against a garden wall, breaking his nose. This event left a distinct mark on his appearance. Although his childhood was marked by a shy temperament and challenges fitting in at school, Adams found solace in the outdoors. His father encouraged his interests by providing a well-rounded education that included private tutoring in music and academics.

By his early teens, Adams had developed two major passions: the piano and nature. At the age of 12, he received a Kodak Brownie camera, a simple and inexpensive box camera that introduced millions of Americans to photography at that time. This small gift would prove life-changing for Adams, as he grew more fascinated with capturing images of the grand landscapes that surrounded him. Visits to Yosemite deepened his affection for nature and became a lifelong source of inspiration.

The Transition from Music to Photography

In his youth, Adams considered pursuing a career in music, specifically as a concert pianist. However, the call of photography gradually eclipsed his dedication to the piano. He recognized that photography allowed him to combine his artistic sensibility with a unique method of expression—one that captured the vivid beauty of the world in precise detail. By his mid-20s, Adams had fully committed to photography, an art form that would turn him into a defining figure of the 20th century.

Developing the Zone System

One of Ansel Adams’ most significant contributions to the photographic world is the Zone System, a technique he developed in collaboration with photographer Fred Archer. The Zone System is a meticulous method of controlling the exposure and development of film to achieve a desired range of tonal values—from the deepest blacks to the brightest whites. It is based on the principle that every scene has different zones of brightness, which can be measured and adjusted to ensure the final print accurately reflects the photographer’s artistic vision.

For Adams, the Zone System was more than just a technical tool; it was a creative framework that allowed him to pre-visualize a photograph. He believed in imagining the final print in his mind’s eye before ever releasing the camera’s shutter. This fusion of technique and vision set him apart from his contemporaries and influenced generations of photographers who sought a more precise way to create images.

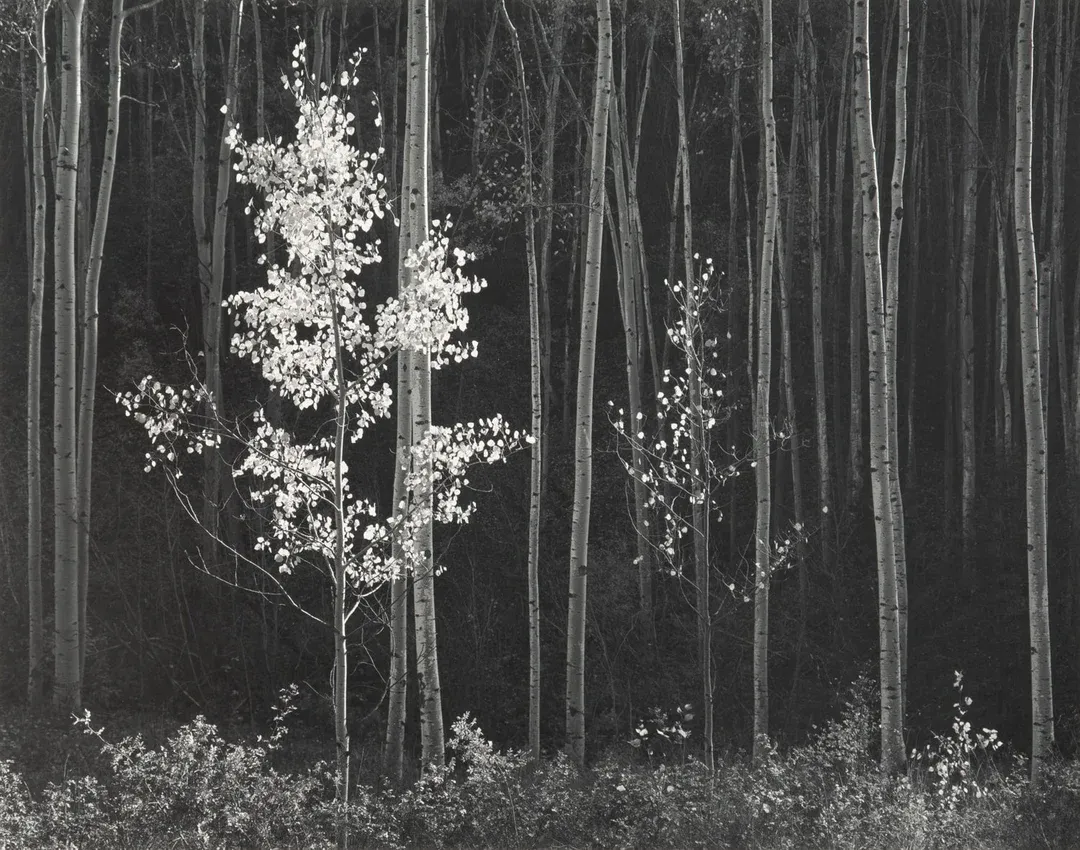

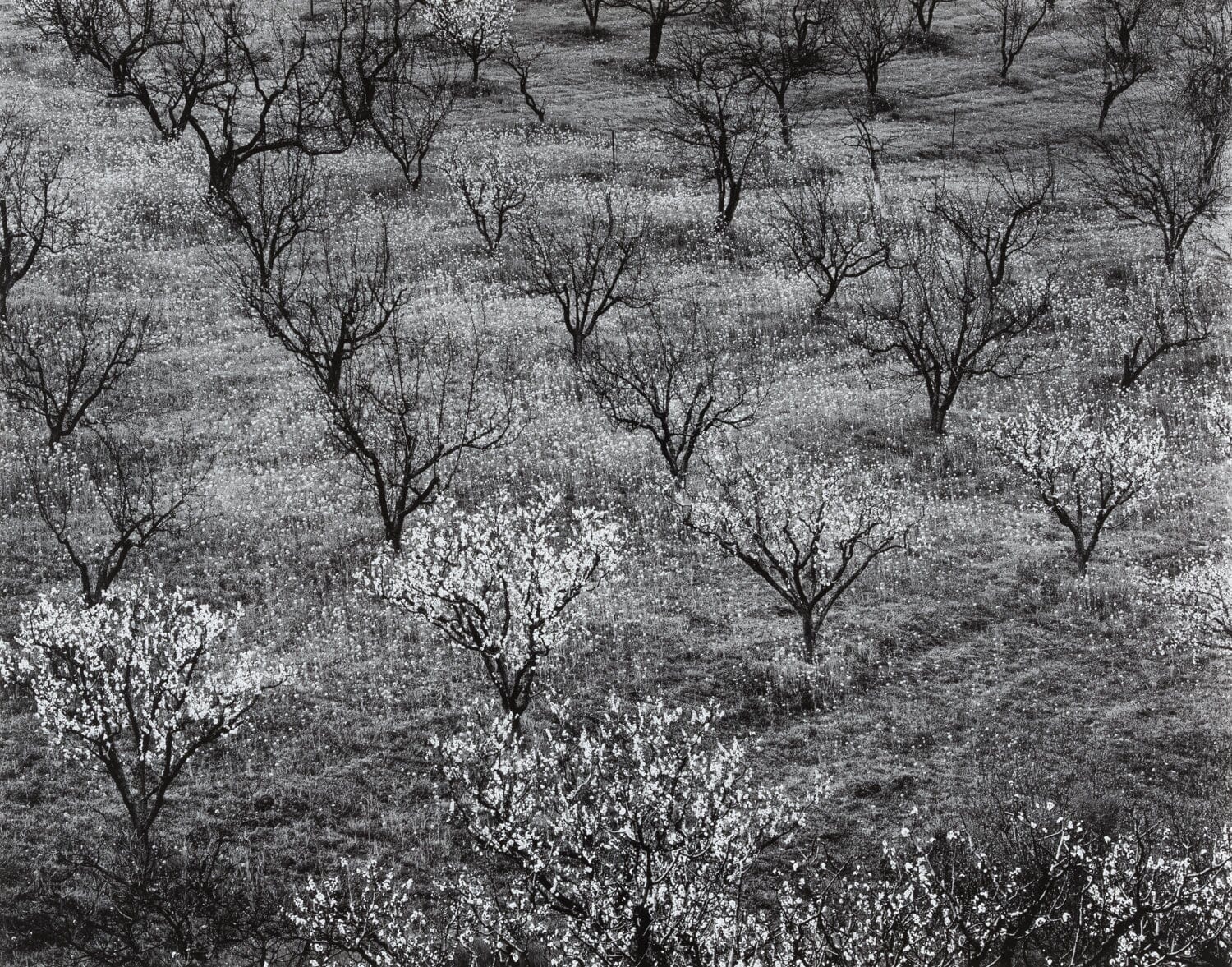

Iconic Photographs and Style

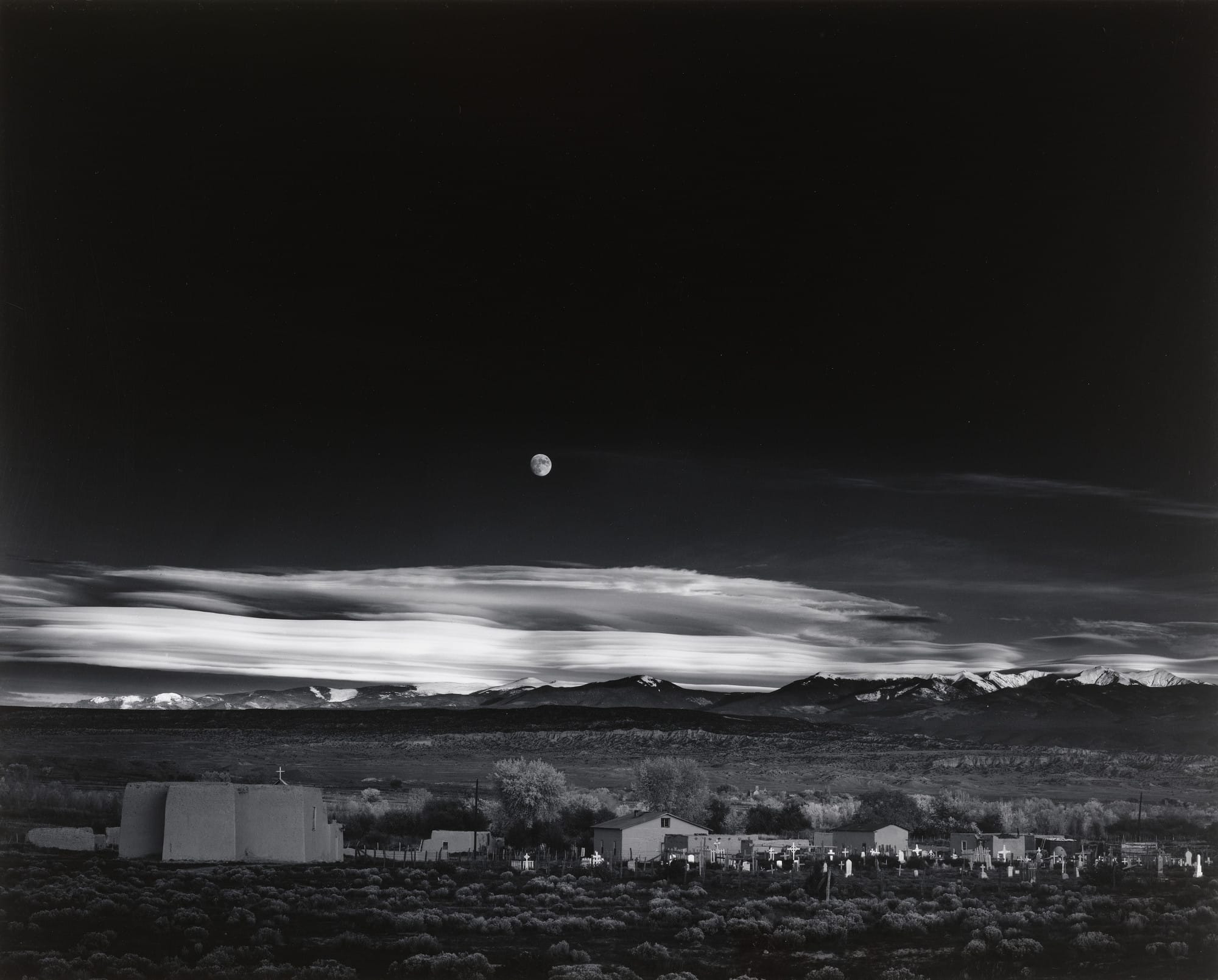

Adams’ portfolio is rich with awe-inspiring images. His photographs often feature dramatic contrasts between light and shadow, crisp details, and impressive compositions. Among his most famous works is “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico” (1941), an image showcasing a small church and cemetery in the foreground and a luminous moon rising over distant mountains. Captured under quickly fading daylight, the final print—meticulously developed—became an iconic piece in photographic history.

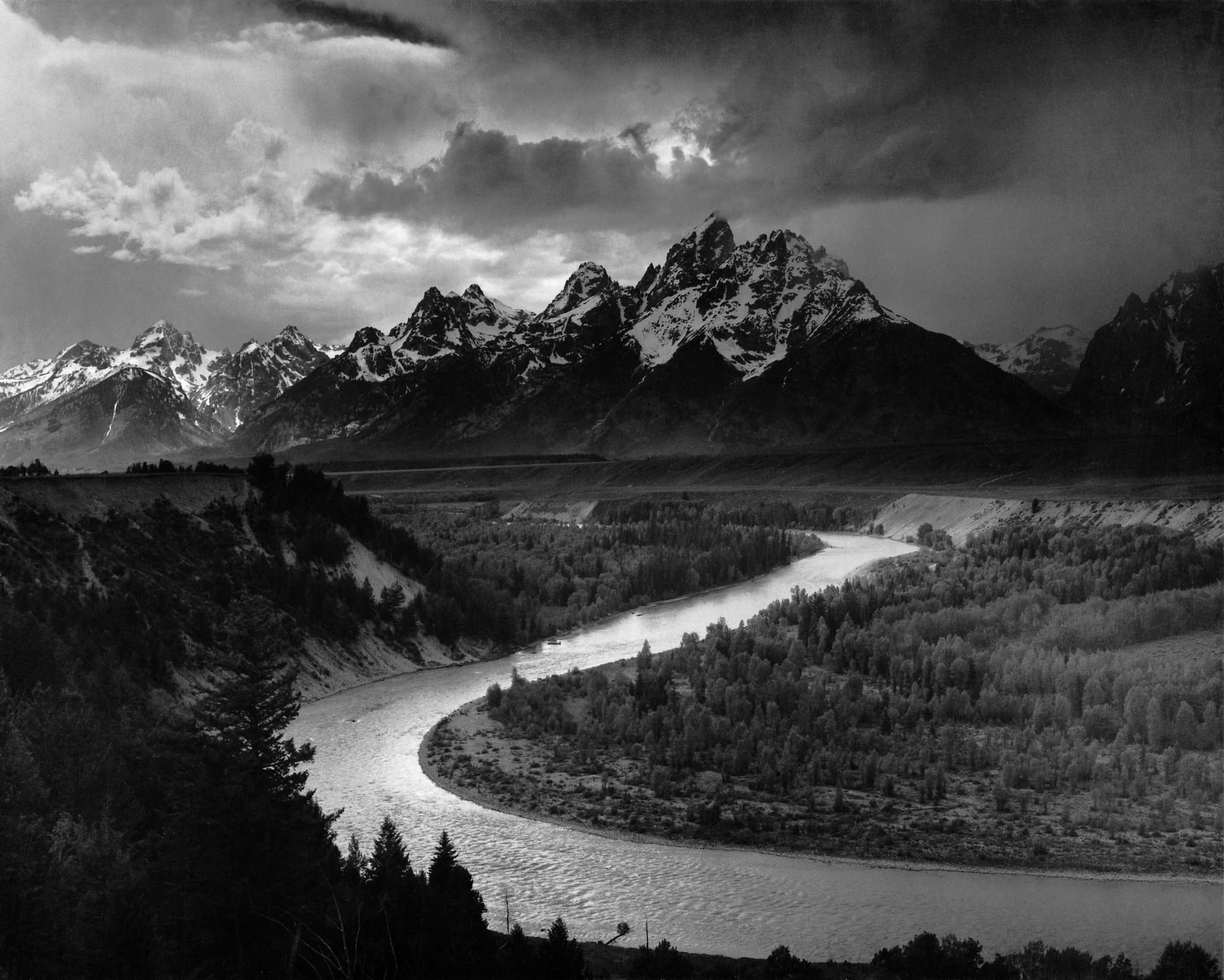

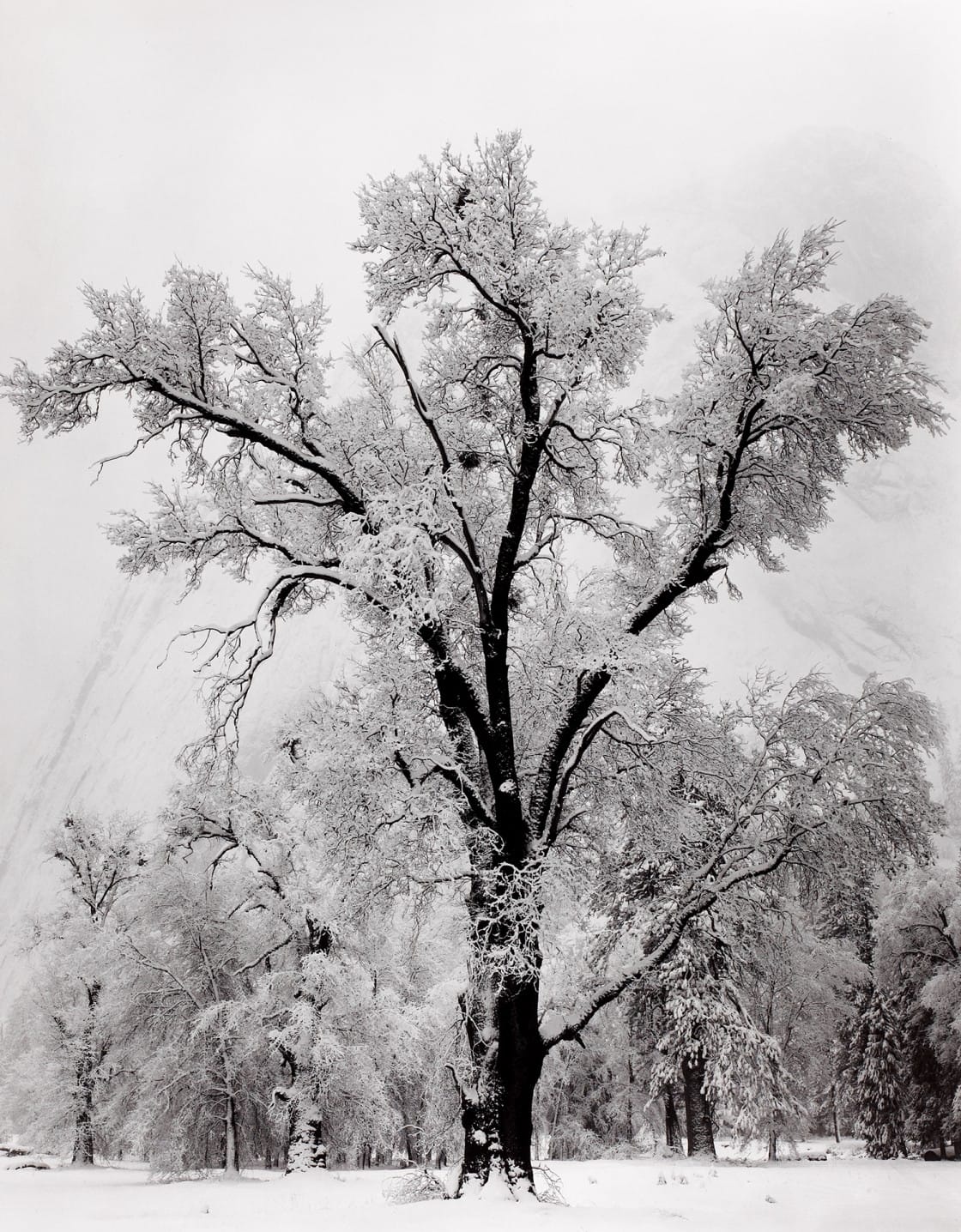

Other celebrated photographs include “Clearing Winter Storm”, featuring sweeping clouds and mist in Yosemite Valley, and “The Tetons and the Snake River”, presenting the rugged peaks of the Teton Range reflected along a winding river. These images exemplify Adams’ approach: carefully planned exposures paired with masterful darkroom techniques.

Environmental Advocacy

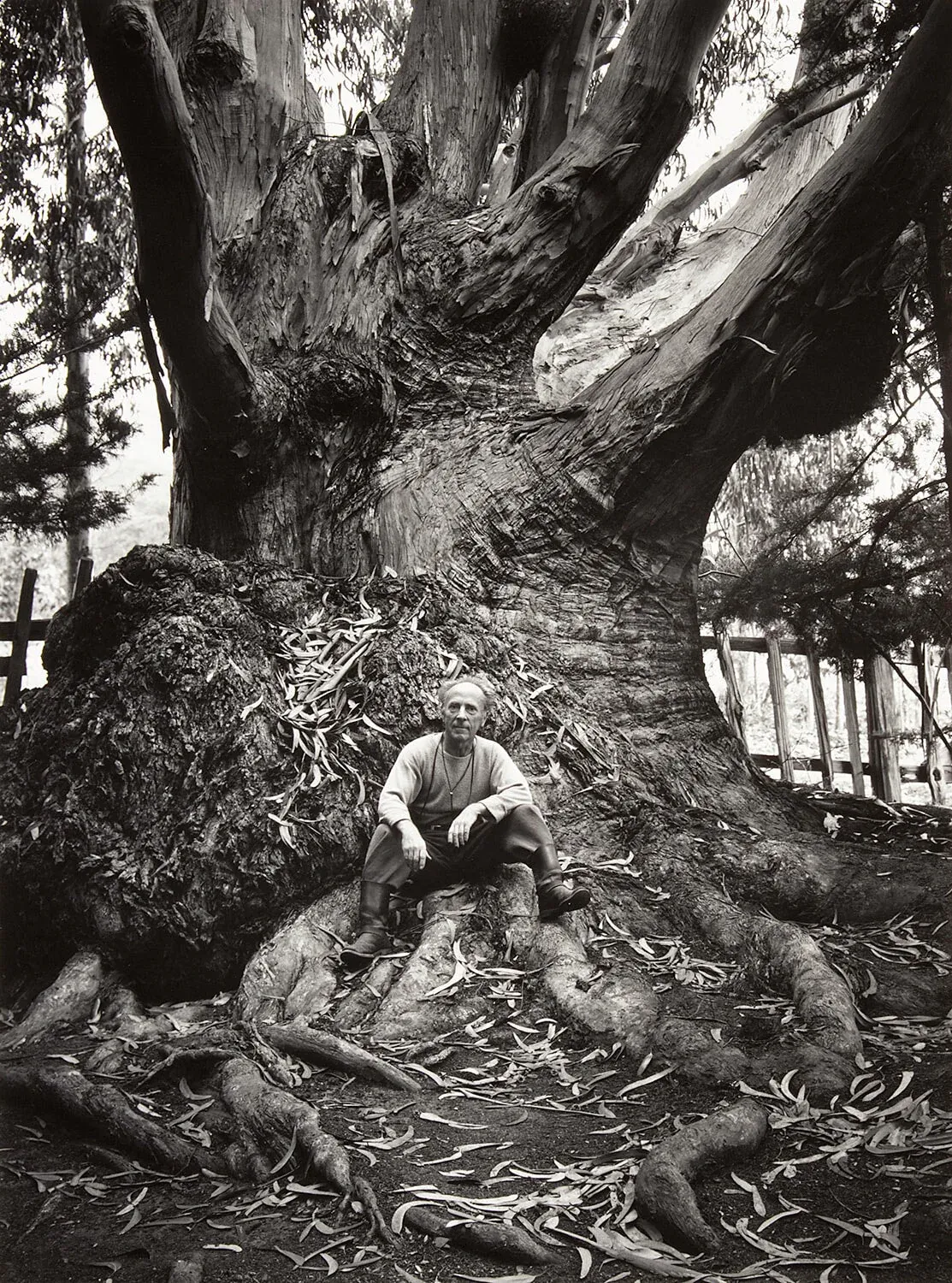

Beyond his creative vision, Adams was also a dedicated outdoors enthusiast who used his photography to champion the protection of wilderness areas. He believed that photographs of majestic landscapes could inspire people to appreciate and safeguard natural treasures. Adams joined organizations such as the Sierra Club, which remains one of the most influential environmental groups in the United States. He spent decades working to preserve places like Yosemite National Park and the national parks system as a whole.

In many ways, his art and his appreciation of the outdoors were inseparable. Adams testified before Congress on matters of conservation and contributed to growing public awareness about the fragility of ecosystems. His images served as both artistic masterpieces and powerful reminders of the need to conserve wild spaces.

Legacy and Influence

Ansel Adams left an indelible mark on photography. His technical breakthroughs, especially the Zone System, continue to influence students and professionals alike. In an age of digital photography, his emphasis on pre-visualization and careful tonal control informs modern editing techniques. Photographers using digital cameras still talk about “exposing to the right” or adjusting “dynamic range,” which aligns with Adams’ time-honored principles.

Adams also served as an early advocate for recognizing photography as a legitimate form of fine art. Institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York showcased his work, helping to elevate photography into a realm typically reserved for painting and sculpture. Young photographers can still learn from his attention to detail, mastery of craft, and unshakable respect for the natural world.

Conclusion

Ansel Adams is much more than the iconic landscapes that continue to captivate viewers. He was a pioneer of photographic technique, a staunch defender of national parks, and a visionary artist who recognized early on the power of images to inspire and to create change. His methods, principles, and contributions to both art and environmental conservation remain integral to photography courses and environmental studies alike. For high school students interested in photography—whether film or digital—studying his life and work offers invaluable lessons on dedication, innovation, and the transformative power of art.

Little Known Facts

Below are a few lesser-known or lighthearted facts you might weave into your article about Ansel Adams, helping to give students a more personal or entertaining glimpse into the artist’s life. You could include these in a brief section near the end of your piece under a heading like “Little-Known Facts” or “Fun Details About Ansel Adams.”

1. Early Piano Aspirations

• Fun Fact: Before fully dedicating himself to photography, Adams seriously pursued a career as a concert pianist. He even practiced the piano up to six hours a day in his teens. His love of music often inspired the rhythms and sense of composition in his photographs.

2. Carmel City Councilor

• Unexpected Civic Role: Adams once served on the Carmel (California) City Council in the 1960s. In that role, he championed responsible planning and preservation, reflecting his passion for both the arts and the environment.

3. Humor in the Darkroom

• Anecdote: Friends and colleagues recall Adams as having a subtle sense of humor. He would sometimes playfully refer to the darkroom as his “creative cave.” While he was methodical in his work, he could lighten the atmosphere by poking fun at the tediousness of waiting for prints to develop.

4. Moonrise Variations

• Ever-Changing Masterpiece: One of Adams’ most iconic photos—Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico—had countless variations in the darkroom. Because Adams continually refined his printing technique, later prints often looked slightly different from earlier ones, which is unusual for a single image.

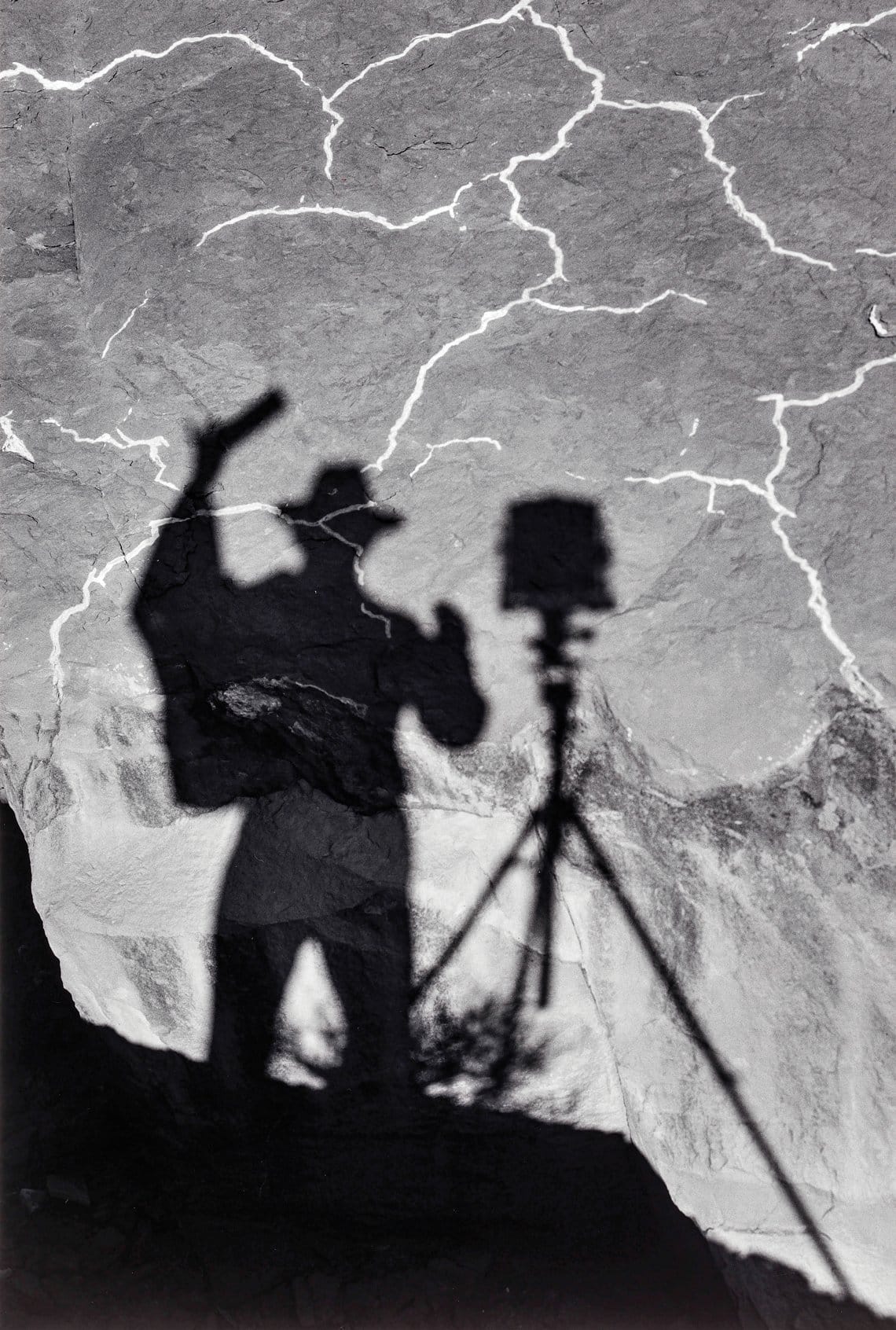

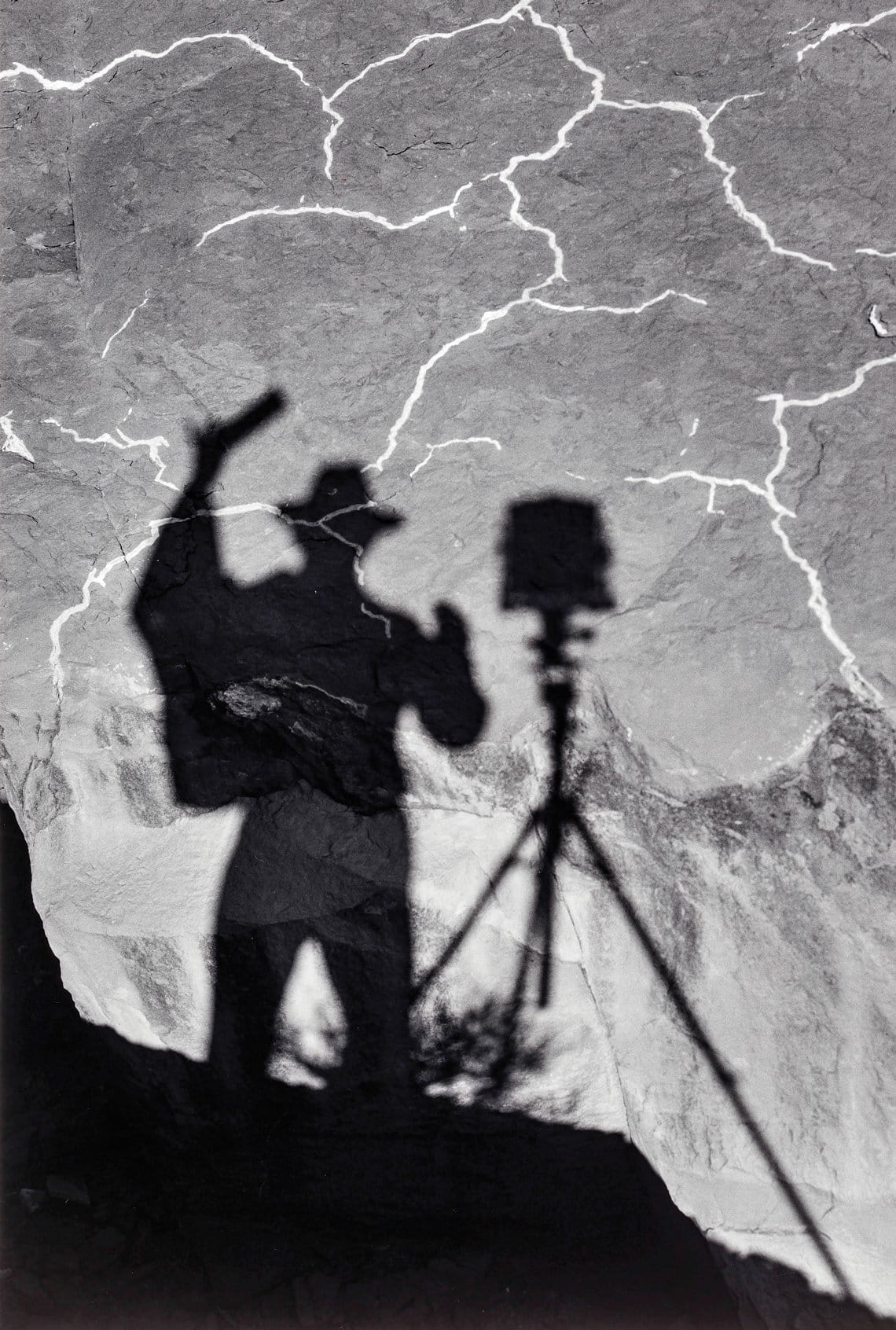

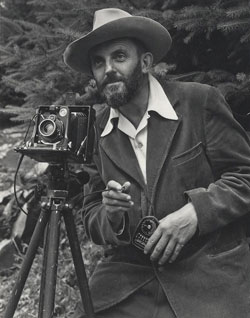

5. Adventure Photography (with a Donkey)

• True Trailblazer: In his younger days, Adams would sometimes head into the backcountry with a pack donkey (nicknamed “Mistletoe” in some accounts) carrying his heavy large-format camera, lenses, and tripod. The sight of Adams, camera gear, and donkey trekking up mountain trails became a familiar image among Sierra Club enthusiasts.

6. Color Photography Skeptic

• Did You Know?: Though Adams experimented with color film, he remained committed to black-and-white photography. He felt that color images lacked the precise control over tones and moods he achieved with grayscale prints, so color photography never dominated his portfolio.

7. He Once Printed a Photo Wrong—and Loved It

• Happy Accident: A darkroom legend says that Adams once accidentally printed the wrong exposure settings for a negative, creating an unusually dramatic image. Rather than discarding it, he saw artistic merit in the variation and kept it—underscoring his openness to serendipity.

8. Clashing with a Condiment

• Quirky Opinion: According to one lighthearted story, Adams famously disliked ketchup and even mentioned it in a letter, labeling it “the bane of gastronomic joy.” While not exactly life-changing, details like this reveal his playful side and everyday preferences.

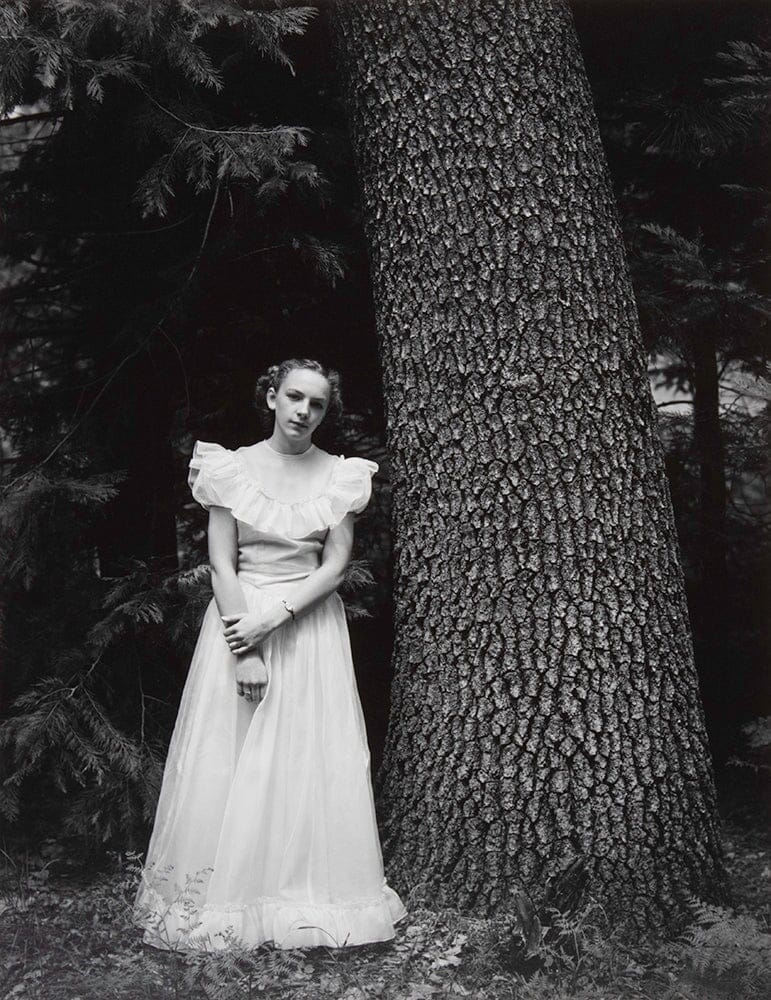

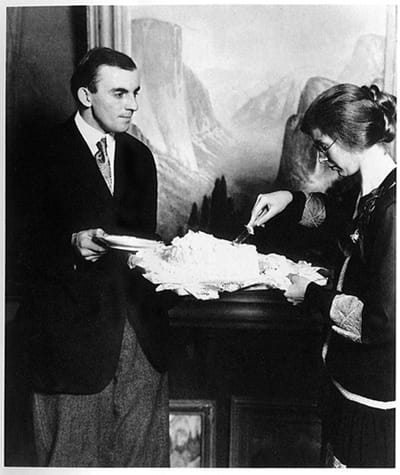

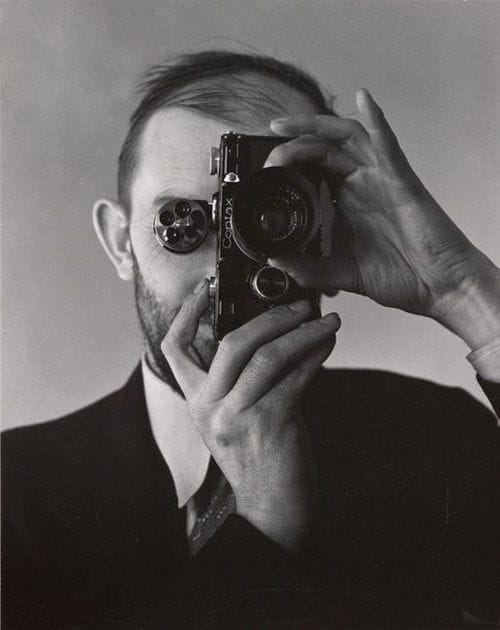

Photographs by: Ansel Adams

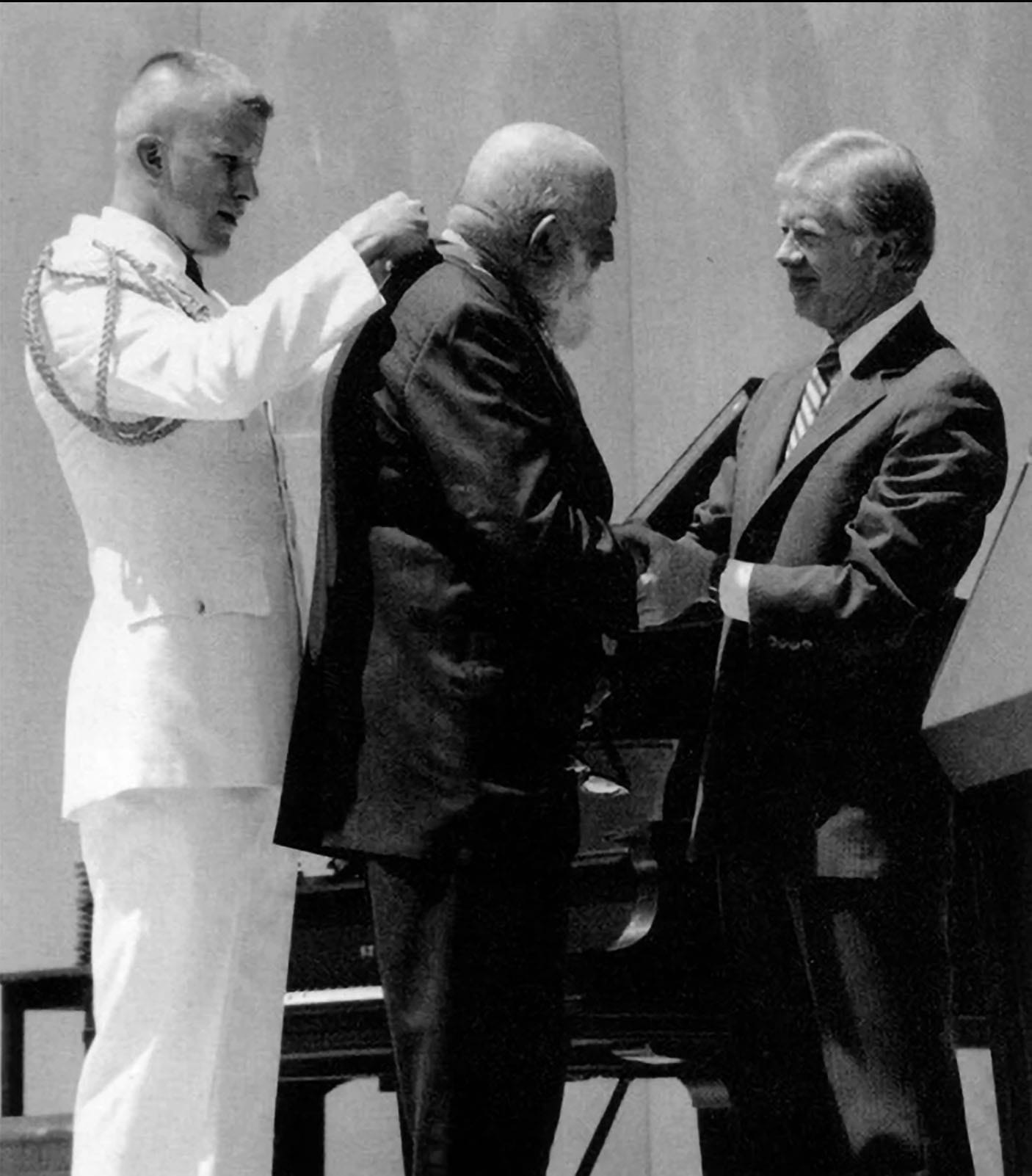

Ansel Adams with Presidents

Ansel Adams with Presidents Lyndon Johnson, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter

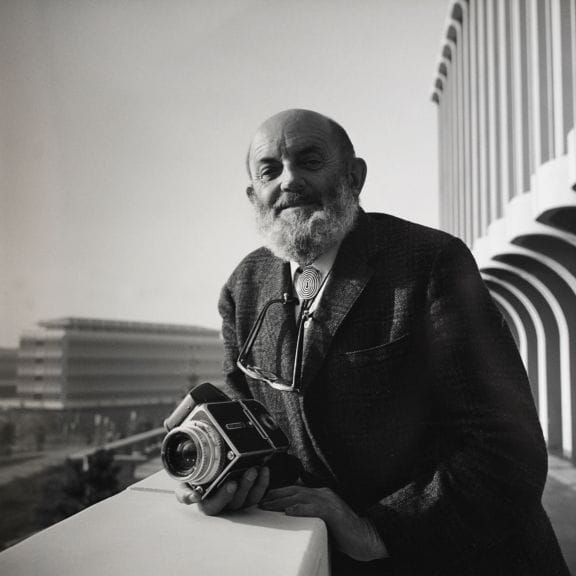

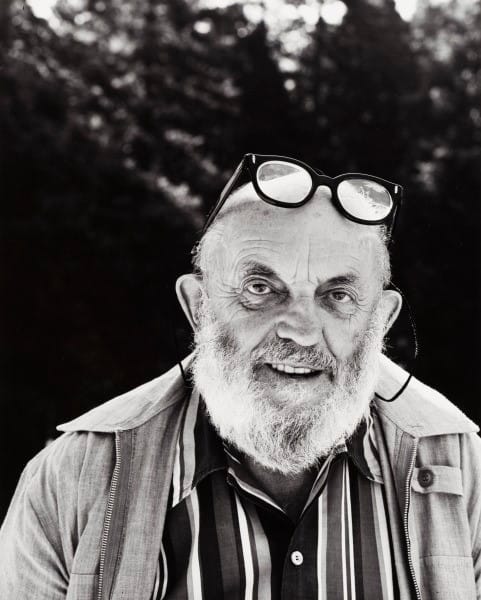

Photographs of Ansel Adams

Additional Resources for Ansel Adams

References for Main Article

1. Alinder, Mary Street. Ansel Adams: A Biography. Bloomsbury, 1996.

2. The Ansel Adams Gallery. “Biography of Ansel Adams.” www.anseladams.com

3. Ansel Adams and the National Parks, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov

4. “Ansel Adams.” The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), https://www.moma.org

5. Adams, Ansel. The Camera, The Negative, The Print (Ansel Adams Photography Series). Little, Brown and Company, 1995.

References for Little Known Facts

1. Alinder, Mary Street. Ansel Adams: A Biography. Bloomsbury, 1996.

2. Ansel Adams Gallery. “Biography of Ansel Adams.”

3. Sierra Club. “Ansel Adams’ Legacy and Conservation.” Sierra Club Bulletin, various issues (1920s–1970s).

4. Szarkowski, John. Looking at Photographs: 100 Pictures from the Collection of The Museum of Modern Art. New York: MoMA, 1973. (Includes commentary on Adams’ prints and darkroom anecdotes.)

5. Alinder, Mary. “A Closer Look at the Man Behind the Lens.” Lecture at the Yosemite Conservancy, 2012. (Contains personal stories and humorous details.)